THE ISHTAR OF OPERA

What if the real historical Jesus was someone quite different from what we’ve been told? What if he was born a bastard, kept a lover and then married her? What if Mary Magdalene, his faithful disciple, was not the legendary prostitute turned penitent? What if we had the chance to meet the authentic Jesus and Mary Magdalene? These are the questions that arise from Mark Adamo’s The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, which premiered with San Francisco Opera this week. But the bigger questions reside in the score and libretto. Without drama, music of  importance, or a compelling human story, we are left with an opera that functions purely at the level of concept. It’s a terrifically intelligent and multifaceted idea, but it has yet to be realized.

importance, or a compelling human story, we are left with an opera that functions purely at the level of concept. It’s a terrifically intelligent and multifaceted idea, but it has yet to be realized.

Adamo’s full-length opera draws on the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 and the Gnostic Gospels, where the Magdalene is a heroine celebrated as Jesus’ most beloved apostle. This radical reinterpretation of Magdalene as a shaping force in the early church stoked the fires of a modern feminist challenge to conventional Christianity. In 2009, an opera was commissioned by SFO to draw on the Canonical and Gnostic Gospels, and to — in Adamo’s words — “reimagine the world from the eyes of its lone substantial female character.”

It all seems timely and relevant, especially given the interest in Magdalene since Dan Brown’s best-selling The Da Vinci Code went one step further by claiming she was Jesus’ wife. The raw ingredients Adamo had to work with offered a truly juicy  mix of sexuality and spirituality, one that promised to upend traditional thinking about the New Testament and rewrite the role of Christ himself.

mix of sexuality and spirituality, one that promised to upend traditional thinking about the New Testament and rewrite the role of Christ himself.

So what went wrong? The libretto, perhaps too conscientiously footnoted and researched, never relaxes enough to take the necessary creative liberties to present an interesting story. Adamo seems chained to exact quotes from the gospel — which he renders in simple verse rhymes — without realizing that he ends up with a pile of excerpted phrases that are rendered insignificant and indecipherable. The central theme of the opera itself is summed up in this convoluted phrase:

WHEN YOU’RE NOT AFRAID TO LOSE SOMEONE/

YOU’LL HAVE UNDERSTOOD/

HOW CAN YOU LOSE YOURSELF/

SO YOU CAN FIND YOURSELF/

FOR GOOD

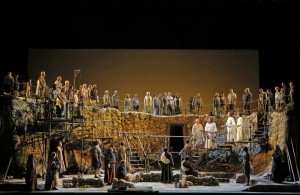

The characters of Yeshua (a.k.a Jesus) and Magdalene function more as cardboard cut-outs — parroting proverbs that dutifully align with the bare outline of the life of Christ — than as deep, living, breathing people. This opera is a chaste and subdued rendition of the supposed sexual hunger Jesus and Magdalene had for each other. The frank sexual longing that existed in Jesus Christ Superstar is missing here, as is  the complexity of adult love: The two are covered in long white robes resembling Victorian nightdresses, and when they finally bed, attendants throw a huge white towel over them.

the complexity of adult love: The two are covered in long white robes resembling Victorian nightdresses, and when they finally bed, attendants throw a huge white towel over them.

Also, we never get a sense of what Mary Magdalene and this Jesus actually stood for, so it is difficult to care in the end that their message was suppressed. The creators want us to care about them, but the whole affair seems forced, overblown and trite. What little narrative there is lacks dramatic tension and surprise – not because we know the ending, but because neither character seems to have anything to say.

The potentially inflammatory, blasphemous love between these two comes across as stale pabulum for the New Age crowd, marching to the call of “Let it go,” a watered down variant (I can’t call it an aria) of “Let it be.” “Tell them what we learned,” Yeshua implores, as, resurrected, he slowly rises vertically from a floor covered by mist like a scene from Phantom of the Opera. “Tell them how we learned we were designed, for love of every kind.” “I shall tell them,” Mary echoes, but we are left wondering what there is that she could possibly say. There is not much that even the  most talented opera stars can do with a libretto spouting Jonathan Livingston Seagull-like platitudes, such as “You are – I am/We are part of a design/Our journeys intertwine/In the same design.”

most talented opera stars can do with a libretto spouting Jonathan Livingston Seagull-like platitudes, such as “You are – I am/We are part of a design/Our journeys intertwine/In the same design.”

The only fun moments are the asides the chorus makes, literally singing biblical citations when a character calls for them (it’s the first chorus I’ve heard sing “Ibid”). Sung footnotes and citations aside, this is opera, not Ulysses. On experiencing new opera, one wants one’s soul to take flight, not hunker down to the texts to check out biblical references.

The music in Mary Magdalene is primarily recitative and tedious. There are arias listed, but they are hard to label as such. The songs do not generate much emotion, and it is difficult to identify a piece that would appeal to a general audience, let alone enter the repertoire. While contemporary opera is not known for showcasing the  type of music that moves your heart, it can produce music that is unforgettable and powerful. Unfortunately, such is not the case here.

type of music that moves your heart, it can produce music that is unforgettable and powerful. Unfortunately, such is not the case here.

Sadly, baritone Nathan Gunn’s Yeshua lacks charisma; he’s wooden, passive and dour — not the kind of guy you think of when Magdalene desires “body and mind.” Gunn’s singing is also frequently drowned out by the orchestra, through no fault of conductor Michael Christie.

There are successes in the production. As Adamo’s misunderstood heroine, the enchantingly beautiful mezzo-soprano, Sasha Cooke — her lank auburn hair in a loose ponytail — fills the War Memorial Opera House’s huge concert hall with her luminous voice, characterized by its sensational precision and tone. William Burden and Maria Kanyova, as Peter the apostle and Mirium (mother of Jesus), effectively play their roles with passion and angst.

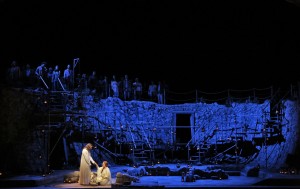

David Korins’ set, presented as a mutli-level archeological dig, is a masterpiece of economy with its spartan rocks, tunnels and sand – apropos for the 21st century chorus of onlookers, dressed in jeans and chinos by Constance Hoffman. The space,  however, seems constrained, and director Kevin Newbury has trouble moving the characters around.

however, seems constrained, and director Kevin Newbury has trouble moving the characters around.

Chistopher Maravich’s lighting is one of the most exquisite elements of this performance. When dawn comes after the first night of love between Yeshua and Mary, the periwinkle early morning sky is set against tiny glowing candles scattered across the sand to look like delicate blooms in their first stage of flowering, encapsulating the intimacy and silent fragility of the moment. Later, the entire stage is memorably bathed in pulsing vermillion as Yeshua is crucified, save one white spotlight on Peter as he denies Yeshua three times, throwing sharp focus on his grief.

But therein lays the problem. The production may be beautifully lit, but if Jesus is the light of the world, isn’t that light supposed to come from within?

photos ©Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

The Gospel of Mary Magdalene

San Francisco Opera

War Memorial Opera House

scheduled to end on July 7, 2013

for tickets, call 415-864-3330 or visit http://www.sfopera.com